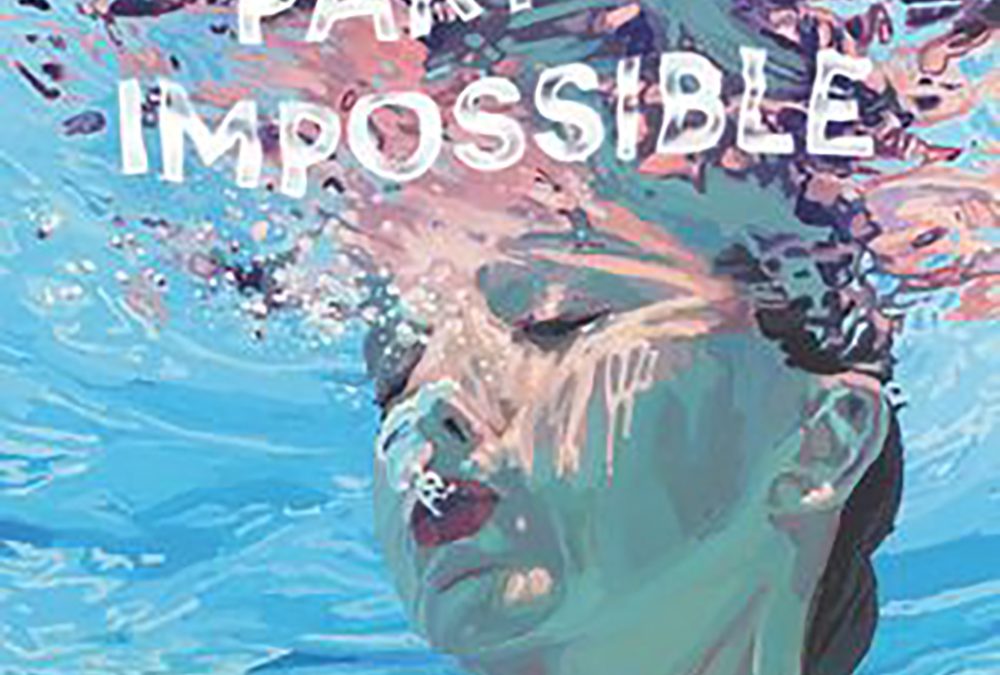

By Sarah Tomp; HarperTeen

Teenager Ria Williams is a skilled diver. She is on track to compete at the Olympic level, but injury forces her to abandon this dream and walk away from all she’s known. With time on her hands to reevaluate what she wants, she finds herself increasingly drawn to Cotton, an old friend with autism who has a passion for cartography and cave exploration. As their friendship blossoms into something more, Ria is pushed to reflect on the dynamic she shared with her former diving coach, Benny — to finally see him for the abuser he was. When an offer comes along that could reignite her diving career — at the cost of having Benny back in her life — she struggles to separate the thing she loves most from the trauma she has endured.

Rather than exposing the reader to repeated examples of Ria’s physical and mental suffering, the abuse looms on the periphery of the narrative for much of the novel, and this is effective on a number of levels. First, it reflects the sense of repression and denial experienced by many victims. Sarah Tomp shows the subconscious ways Ria has attempted to rationalize and excuse Benny’s behavior as a means of self-protection. Secondly, the reader is given enough context and information to understand what has been happening long before Ria is ready to admit it even to herself. This creates sympathy for the protagonist, while also establishing a sense of inevitable climax — at some point she will surely be forced to face up to the truth. Finally, it’s indicative of Tomp’s sensitive decision to focus predominantly on the hidden mental ramifications of abuse, rather than the more easily sensationalized physical details.

Though the book lacks insight into Benny’s mindset, which could have offered a fascinating alternative take on the relationship between victim and abuser, the supporting characters are drawn well enough to widen the novel’s thematic scope in other ways. Cotton’s autism is handled with due care, while a subplot concerning his missing sister serves as an effective mirror for Ria’s arc about the need for closure. Meanwhile, Ria’s friendship with a fellow diver provides a look at the unique brand of rivalry that can exist between teenage girls, and the prevailing notion of sisterhood that can ultimately help them overcome it.

In addition to the emotional investment in the characters, the short chapters and readable prose make this a book that is easy to fly through. However, it’s not uncommon for novels aimed at young adults to suffer from moments of awkward dialogue — the author becoming briefly visible through their attempts to adopt a narrative voice that feels authentically youthful. The Easy Part of Impossible is no exception, particularly throughout Ria and Cotton’s romantic subplot, with several scenes indulging in genre tropes that feel overly familiar.

Another consistent thread that is highly successful, however, is the book’s look at the benefit of sports on our physical and mental well-being. Ria suffers from attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Diving provides an ideal outlet for her excess energy, while also bringing much needed focus and structure to her days. When injury temporarily prevents her from diving, running and caving prove vital lifelines. Girls and people with mental or behavioral health conditions have historically been excluded from sports, and there is a notable lack of media that actively encourages their participation. It’s admirable that this novel is able to highlight the dark side of the sporting world without dismissing its many positive qualities. Indeed, if participating in organized sports is what puts Ria at risk in the first place, the opportunities and empowerment that diving offers may prove to be her salvation.

Book reviewed by Callum McLaughlin