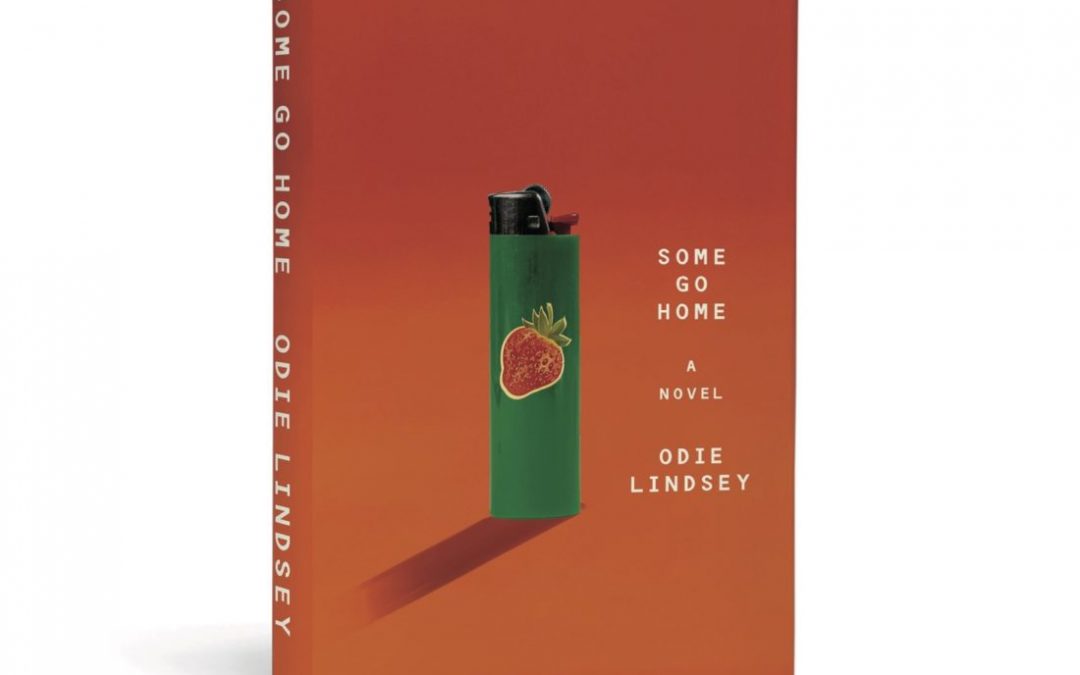

By Odie Lindsey; W.W. Norton & Company

At first blush, Some Go Home explores veteran Colleen Friar’s acclimation back to her hometown of Pitchlynn, Mississippi following her deployment. Yet the novel also addresses the idea that home is an amalgamation of people and places, lineage and legacy. To that end, Lindsey includes a cross-section of narratives, dating back to the 1960s, that help define the rural town of Pitchlynn and its people. Although Colleen serves as the central character, equally important are many others who appear, each with their own intimate ties to Pitchlynn.

The story begins as Colleen grapples with her homecoming and impending motherhood. Her husband, Derby, possesses the unfortunate legacy of being the son of Hare Hobbs, who many believe to be responsible for killing a local black landowner, Gabriel, and who is soon to be retried for the crime. Derby has done his best in the meantime to distance himself from his father, both in terms of his moral code and identity.

The characters are tethered to one another by the Wallis House, a place that serves as a character in and of itself as it whispers the racist legacy of Pitchlynn as well as its foundation of classism. In the 1960s, Gabe, the man Hare allegedly murdered, inherited a portion of Wallis farmland from his grandfather that had been a bribe to cover up indiscretions of Wallis’ forebears. In a flashback, Gabe feels irrevocably tied to the land due to the privileges and status that come from landownership. His strength born of this ownership makes Hare feel threatened. Mr. Wallis, feeling threatened himself by the growing civil rights movement, baits Hare into seeing Gabe as an affront to both his manhood and his social status. He instructs Hare that “there are only two things on this planet that matter, that you either have, or you take: earth and birth.” Wallis subtly belittles Hare for the nefarious purpose of thwarting black advocates for civil rights, knowing he will take action against Gabe.

Secondary characters also grapple with their ties to Pitchlynn and its checkered past. Sonny, Hare’s first son, who possesses intimate knowledge of the events preceding Gabe’s murder, tries to return home to resolve questions about Hare that plague him into adulthood. Dru, heir to the Wallis House, was banned from the town as the result of an unfortunate childhood accident and continually ruminates over returning to Pitchlynn in an effort to settle the angst that consumes her. These characters’ stories serve as a reminder that despite the imprint home may make on us, sometimes we cannot reconcile the difference between what home truly is versus what we perceive it to be.

Ultimately, Colleen must reckon with what it means to go home. At first, she sees motherhood on the horizon, yet she is briefly “yanked under by a riptide of past trauma.” Her journey to being a parent requires she make peace with such traumas to truly move forward. In order to make a home for her twins, she must find her own way back home. This idea serves as an underpinning of the very heart of the work: We are stewards of the land and our children. The two are inextricably joined.

While readers may find solace in Colleen’s attempts at catharsis, Lindsey leaves many characters’ conflicts somewhat unresolved, perhaps to invoke a sense of realism. This lack of resolution is disappointing given that the reader also becomes invested in the secondary characters. At times, it feels as though each of them, particularly Dru, could warrant their own leading role.

Some Go Home explores how a place can leave an indelible mark. It is a reminder of how race, class and power are all tangled in American soil—both historically and presently, and of the fortitude and resilience necessary to work the knots.

Reviewed by Jane McCormack